With Umbrella, Scotch and Cigarettes – An Unauthorised Guide To The Avengers Series 1

Following their excellent The Strange Case of the Missing Episodes, writers Richard McGinlay and Alan Hayes have gone even deeper into Avengers esoterica in With Umbrella, Scotch and Cigarettes – An Unauthorised Guide to The Avengers Series 1. The book focuses on the production history of the lost season, detailing everything from how The Avengers began right through to Ian Hendry’s departure in the aftermath of an actors’ strike and the ascension of Patrick Macnee to the lead role. Drawing on information from scripts, other histories of The Avengers, star biographies, and production notes, the authors paint the most comprehensive picture yet of the lost season.

McGinlay and Hayes open their book with a detailed depiction of the inception of The Avengers, initially conceived as a showcase for star Ian Hendry after the folding of his short-lived drama Police Surgeon. The addition of Patrick Macnee as “undercover man” John Steed, Ingrid Hafner as Dr. Keel’s nurse and assistant Carol, and a slew of producers, directors, and writers would make The Avengers what it eventually became: a combination of British noir, spy show, and genre-defying pastiche. From the rather harried early days of the show (that included Macnee being told that his character, already undeveloped in scripts, was not developed enough), The Avengers quickly became a sort of British noir, permeated with underworld characters and almost-anti-heroes.

Following their in-depth discussion of the show’s birth, McGinlay and Hayes cover each episode in turn. They divide their discussion into smaller sections covering existing archive materials, a general plot synopsis, production, location, star/writer/director biographies, miscellanea, contemporary press/media coverage, and finally a “verdict” on the episode itself. The division works well to present the complexities of production in a fairly readable manner, allowing writers and readers to delve into the various issues and occasional anecdotes that permeated the show. Some of the episodes have a fascinating production history and the book does an admirable job of charting the ebbs and flows of characters and plots, with new emphasis on the parts that various writers and directors played in creating the show.

With Umbrella, Scotch and Cigarettes is quite readable, an impressive feat for a book concerned with the missing episodes of a niche TV show. The production histories are fascinating, as are the individual bits of information about different episodes. Some episodes are more comprehensively covered than others, largely due to the availability of material, but every one is treated with interest and respect. Although I rarely enjoy looking into extensive production circumstances, I found the behind-the-scenes look into this series more interesting with each word.

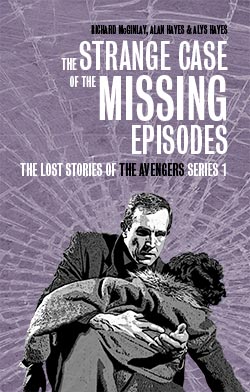

There are problems, however, mostly to do with the more critical and analytic aspects of the book. The authors have an unfortunate tendency to editorialize in the “verdict” sections of their episode overviews, providing small reviews of the episodes based upon available sources. The verdicts appear out of keeping with the otherwise scholarly and historically-minded book; what is more, they are assessments of episodes which the reader cannot hope to question or refute, as the only material presented in the book is of general plot synopses and production history (script excerpts are confined to the other McGinlay/Hayes book The Strange Case of the Missing Episodes). The reviews come off as an attempt to pass judgment on character actions in a series that no one has actually seen, with the reader in particular left faced with the authoritative statements of the authors over against no other ability to fully assess the episodes for themselves. It would have been more efficacious to provide a deeper critical analysis of episodes, based on extant information, rather than the limited reviews here. Having read The Strange Case of the Missing Episodes and watched the available materials, I am neither as enamored with Keel’s character as McGinlay and Hayes – in fact, I think they give the character far too much credit, and rather short shrift to the complexities of John Steed – nor do I share some of their assessments of the episodes or the characters. This is a critical disagreement only, but McGinlay and Hayes fail to support their reviews or assessments with in-depth analysis.

At times, it appears that the authors cannot decide whether they are writing a popular work or a serious scholarly investigation into the series – the effect is that some elements of the series appear to be elided over, while others (like the biographies of directors, writers, and actors) delved into with greater depth. At the same time, Hayes and McGinlay occasionally employ coy language in discussing the sexuality or violence present in The Avengers. I was particularly bothered by the use of phrases like “unable to come to terms with losing the woman he loved,” just prior to describing a director’s almost murderous attack on his former girlfriend, a director of programmes – an occurrence that caused a production delay on one episode. This sort of editorializing seemed an out of place and somewhat saccharine treatment of the story. That the authors are otherwise rather coy about their discussion of Steed’s “philandering” and relationships with women, as well as the darker sexual and violent aspects of the series, seems to bespeak an editorial inconsistency that sometimes mars episode discussions.

As with The Strange Case of the Missing Episodes, we see no photographs or images (save for a few lovely drawings of our heroes by artist Shaqui Le Vesconte), which again makes some of the episodes and productions difficult to visualize. The unwillingness of the authors to provide more comprehensive plot synopses makes it equally difficult to fully assess the episodes as fictional productions. Granted that those synopses are in the earlier book, it would behoove the reader to have both books on hand. I would encourage the reader to purchase both With Umbrella, Scotch and Cigarettes and The Strange Case of the Missing Episodes, and read them in tandem with each other to get a more complete picture of the season.

Finally, there is the matter of the appendices. Hayes and McGinlay have thought it fit to include an examination of several unproduced scripts for The Avengers, as well as discussions of “later” adventures of Steed and Keel, including comic strips that appeared in the 1960s and a later novel from the 90s. While the unproduced stories are fascinating, I cannot quite get behind the inclusion of a rather in-depth discussion of Too Many Targets, the novel by John Peel and Dave Rogers. Not only does it have little to do with a “guide to Series 1,” it really should be forgotten by the annals of time as a rather paltry form of fan fiction (of which there is also a plethora available on the Internet). If an appendix was absolutely necessary for this book, the authors might have been better served by covering the adaptations of the existing scripts in the Big Finish productions, if just a general overview of that resurrection attempt.

My objections to this book, however, are vastly outweighed by the positives. To my knowledge there has not been a more in-depth discussion of the first season of The Avengers, and certainly not one as accessible and interesting. Once more, McGinlay and Hayes paint a comprehensive picture of this season, giving us invaluable insight into the harried early years of a show that would eventually influence everything from James Bond to Marvel comics. As with The Strange Case of the Missing Episodes, I found myself longing for the original productions, to see Steed and Keel rushing through London, tackling underworld characters, drinking gallons of Scotch, and grappling with all the excitement and danger that live television could offer. As it is, we can only imagine what it all looked like – but With Umbrella, Scotch and Cigarettes goes a long way to fueling that imagination.

Both The Strange Case of the Missing Episodes and With Umbrella, Scotch and Cigarettes can be purchased via the following links:

Lulu: The Strange Case of the Missing Episodes, With Umbrella, Scotch and Cigarettes,

Hidden Tiger: The Strange Case of the Missing Episodes, With Umbrella, Scotch and Cigarettes

Amazon: The Strange Case of the Missing Episodes, With Umbrella, Scotch and Cigarettes