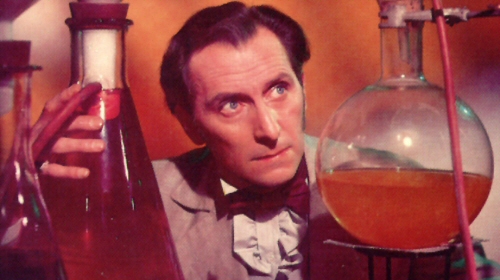

In case you missed it, I’ve got a bit of thing going on with Vincent Price. It was entirely unintentional, but whenever I want a movie that is guaranteed to be delightful without being too terribly serious, I go for something starring Mr. Price. Because Vincent Price is cooler than you or me, and he knows it.

So imagine my excitement when I realized that I had not sene THE movie that more or less made Vincent Price into Vincent Price. That is to say, up until Dragonwyck, Price had been a standard supporting player, appearing mostly as second-class villains or smarmy pretty boys (Laura). Despite a pretty creepy turn in Samuel Fuller’s Shock, a non-villainous part in The House Of The Seven Gables with George Sanders, and a few minor villain roles, Price had not quite become the gothic creeper we all know and love.

Then along came Dragonwyck. Price plays Nicholas Van Ryn, a New York landlord with medieval sensibilities who falls (kind of) for his distant cousin Miranda (Gene Tierney). But Van Ryn’s wife (Connie Marshall) is in the way, so he’s got to get rid of her before he can marry his pretty cousin and ruin her life too. Meanwhile, the tenants of Van Ryn’s land want out of their rather feudal contract with their master – and are trying to get there with the help of the hunky local doctor (Glenn Langan), who’s also falling for Miranda.

Then along came Dragonwyck. Price plays Nicholas Van Ryn, a New York landlord with medieval sensibilities who falls (kind of) for his distant cousin Miranda (Gene Tierney). But Van Ryn’s wife (Connie Marshall) is in the way, so he’s got to get rid of her before he can marry his pretty cousin and ruin her life too. Meanwhile, the tenants of Van Ryn’s land want out of their rather feudal contract with their master – and are trying to get there with the help of the hunky local doctor (Glenn Langan), who’s also falling for Miranda.

Dragonwyck represents Price’s first real foray into the realm of the gothic villain. His Van Ryn is charming and frigid, a vindictive head-case with delusions about his place in society. He’s a snob, a vicious landlord, a classist, a suppressor of men’s rights, and an apparent believer in the droit de seigneur. He’s also positively gorgeous in a way that I did not really think Vincent Price was capable of being.

But although I watched Dragonwyck for Price, the movie really belongs to Gene Tierney, who plays a sympathetic and remarkably strong young woman. It’s understandable how the daughter of a Connecticut farmer and minister (played, by the way, by Walter Huston, just because) could be seduced by her handsome, wealthy cousin. But at no point does Miranda fall into the common position of gothic heroines. She stands up to her autocratic husband, despising and loving him at the same time. As her illusions are stripped away, she does not become less powerful but more so.

Dragonwyck is a surprising film. It could very easily have fallen into a typical gothic tale of innocence assaulted and corrupted. But none of the characters are stereotypes. Miranda’s father preaches at her, then softens, saying, “Indulge me. You won’t have to put up with me much longer.” Huston plays him as a decent, God-fearing man who wants very much to give his daughter what she desires, even if it does not tally with his beliefs. He is in direct contrast with Van Ryn, who does not believe in God but in himself. This is not just hubris – it is a fundamental aspect of Van Ryn’s character that is more tragic than dangerous. He’s a man imprisoned by his ancestors and wholly incapable of escaping them.

So Dragonwyck exceeds its gothic underpinnings. While there are the requisite secret rooms, creepy servants and haunting portraits, the film produces a complex tale of power and religion, love and possession, the sickly past and potential for the future. It’s a fascinating film, and not just because Vincent Price is beautiful. Although, there’s that too.

![1946 Dragonwyck [El castillo de Dragonwyck] - Joseph L. Mankiewicz - [DVDrip] [XviD 640x480x30] [[01-34-05]](https://suddenlyashotrangout.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/1946-dragonwyck-el-castillo-de-dragonwyck-joseph-l-mankiewicz-dvdrip-xvid-640x480x30-01-34-05.jpg?w=300&h=225)