*This is a reprint in two parts of a paper I wrote for Ed Guerrero’s “Horror, Sci-fi, and Difference” class during my Master’s degree at NYU. With the 30th Anniversary of the release of Ghostbusters coming up this month, I thought it appropriate to post here. Check back next week for Part II!*

‘Funny us going out like this: killed by a hundred-foot marshmallow man.’ –Ray Stantz (Dan Aykroyd) in Ivan Reitman’s Ghostbusters (Columbia, 1984).

One of the more indelible cinematic images of terror and humor of the late twentieth century is that of a gigantic marshmallow man stomping through New York City like a sugary Godzilla nearing the end of Ghostbusters. Ghostbusters itself is one of the more interesting installments of a subgenre typically referred to as horror-comedies, a combination of the explosion of the chaos world of horror with the carnivalesque humor of the comic tradition. A film rife with horrific and apocalyptic imagery, it finds both its terror and its humor in the depiction of the end of the world occurring at 55 Central Park West, with the world destroyed not in a rain of blood and fire and terrible vengeance from above, but puffed sugar.

Ghostbusters may appear to be a frivolous work, but it can and should be taken seriously as a depiction of humor within the horrific. Humor and death are often linked, a way of dealing with the progressively terrifying world. In Bahktin’s definition of grotesque realism, he identifies the physical world of the comic with the organic transformation of death into life:

The ever-growing, inexhaustible, ever-laughing principle which uncrowns and renews it combined with its opposite: the petty, inert, “material principle” of class society…The grotesque image reflects a phenomenon in transformation, an as yet unfinished metamorphosis, of death and birth, growth and becoming (24).

Death and the comic concept of renewal are inextricably linked; the world must end in order to be reborn. If we examine Ghostbusters through this lens, as a serious if also comic examination of death and comic transcendence through parodying and satirizing the end of the world itself, we may elucidate how this film, and other horror-comedies, defy the ineluctable nature of death by literally making fun of the repressive as well as the repressed.

Much horror functions as an expression of the repressed in the form of the monster; much comedy too expresses the repressed in the anarchic vision of the comedian or comedians. The difference is usually that the figure of horror, the monster, is a frightening manifestation of the repressed psyche, a figure that represents gender, class, race or sexual difference that the homogenous society represses. Comedy, by contrast, revels in anarchic expression, the libidinal impulses of the central comedians and their subversion of the social order. Both genres represent eruptions of the chaos world in anarchic visions. They are festive arts that challenge the social order through the creation of fear, laughter, or both.

True festive art…is an art that ultimately celebrates communality, much as any festival does…Festivity is not opposed to depth of meaning. As Bakhtin has noted, certain truths are only available through festive art. A worldview that sees a split between body and spirit limits the value of material existence (Paul 71).

When comedy and horror function in tandem with each other, they form a deep expression of what Paul here defines as a ‘festive art:’

The seriousness of this festivity…resides in the extent to which it inverts the most deeply rooted values of Western culture (71).

In exposing and then making fun of what is most terrifying, we acknowledge the fear, but also the absurdity of the fear. The Ghostbusters participate in a carnivalesque rebellion and joy in destruction usually only open to the monsters of the horror genre. Acting from within the system, the Ghostbusters succeed in subverting the system.

Despite the at times conservative, masculinist nature of its discourse, Ghostbusters inserts its central figures into a material world that refuses to acknowledge the spiritual. The spiritual then manifests itself as something only they can control because they are capable of recognizing its existence. The Ghostbusters have a complicated relationship to the ghosts they capture. They are essentially agents of repression, ‘exterminators’ who arrive to trap and confine the libidinal impulse. Neither the first film nor its sequel address what happens to the ghosts once they are captured, or the moral and ethical complexity of keeping these spirits within a ‘containment unit.’ The three original Ghostbusters are all white middle-class males, educated and, at the opening of the film, acting from within institutional confinement. They are representatives of scientific materialism, all doctors dedicated to the trapping of spirits. They act at the behest of the ruling establishment to arrive and exterminate (or trap) the manifestations of the return of the repressed. In doing so, however, they subvert the system in acts of anarchic destruction.

Athough initially functioning within the establishment, the Ghostbusters come to reject and be rejected by that establishment. The first fifteen minutes of the film sees them confront their first ghost, and lose their jobs at the university. Although they may be educated, they nonetheless appear as working class figures. They are self-described exterminators, essentially the ghost police, identified as such by the uniforms that are janitorial jumpsuits. They live in an old firehouse somewhere on the Lower East Side; their car is a refurbished ambulance. Their names are also indicative of class, religion, and immigrant background: Peter Venkman, Raymond Stantz, and Egon Spengler (Harold Ramis). Throughout the film various members of mainstream WASP society treat them with confusion, contempt and downright aggression. The villains of the film are all representatives of the WASP establishment: the dean at their university (Jordan Charney) and Walter Peck, a representative of the EPA (William Atherton). The establishment, although willing to exploit them, is equally unwilling to trust them. When they are called in, it is unwillingly and with evident embarrassment on the part of the Mayor (David Margulies). The Ghostbusters stand in a liminal position between the libidinal spirits they trap and the material establishment world.

Many of the ghosts in Ghostbusters function as manifestations of libidinal impulses, grotesque representations of the natural body in their obsessions with food, sex, violence, and destruction. Freed from their material existences, the spirits are also free to indulge the libidinal impulses they were perhaps denied in life. The most obvious of these is the famous ‘Slimer’ character, actually referred to as ‘Onionhead’ in the screenplay, the first ghost the Ghostbusters trap (Aykroyd 78). A floating yet apparently physical being—he comes into physical contact with Peter Venkman (Bill Murray) and ‘slimes’ him—his libidinal drive is to eat and drink. He first appears consuming plates of food from a service cart, later eating food from a banquet table and drinking bottles of wine that pass through his spiritual body. His spirit haunts the ‘Sedgwick Hotel,’ an upper class establishment. The Sedgwick is the site for the ultimate in class gluttony. Onionhead consumes the remnants of apparently lavish meals; he invades a sumptuous banquet hall and devours food and wine. We may perhaps view Onionhead as the libidinal manifestation of upper class gluttony, come to revenge itself, a literal return of the repressed.

The Ghostbusters tracking and trapping of Onionhead bears closer scrutiny. They are out of place at the Sedgwick, arriving noisily, dressed outlandishly and carrying gigantic pieces of equipment on their backs. The hotel manager (Michael Ensign) seems uncomfortable in their presence and asks them if everything can be taken care of ‘quietly.’ Harold Ramis remarks, in the DVD commentary, that the Ghostbusters were conceived as Marx Brother-type characters and the Sedgwick Hotel sequence bears this out (Ramis, ‘Commentary’). Comically out of place, they are working class figures in an upper-class setting. Incapable of controlling their equipment, they destroy a large section of the hotel, burning holes in walls, harassing guests, and causing destruction in the banquet hall. They find humor, if not total release, in this destruction:

Ray: I think we’d better split up.

Egon: I agree.

Peter: Yeah, we can do more damage that way.

In hunting down Onionhead, they destroy a chandelier, a full bar, break several tables, glasses and china, and light things on fire. At the conclusion of the scene, they charge four thousand dollars for the destruction they have caused, threatening to replace the captured spirit if they do not get their money.

Whether wittingly or unwittingly, the Ghostbusters actually cause more destruction than the ghost they hunt. Like the Marx Brothers, the Ghostbusters are dependent on the mainstream for their livelihoods; no longer employable as scientists, they have recourse to the working class milieu, but in doing so are able to take revenge, monetary and otherwise, on the system that has rejected them. They may be dependent on the system itself to support them—they certainly do not try to exist outside of it—but they are able to subvert it from within. What is more, they make the system pay for its own destruction. This joy, the humor that comes out of not only Onionhead’s gluttony but the destruction brought about by the Ghostbusters, succeeds in a satiric carnivalesque rebellion that allows the rejected, now working class figures to begin a process of destruction from the inside out.

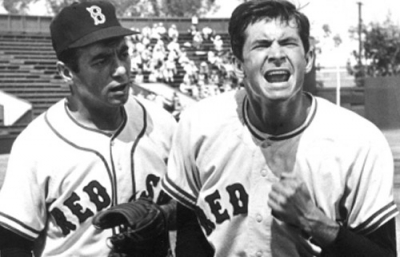

A third of the way through the film, the Ghostbusters are joined by another liminal figure, this one legitimately working class: Winston Zeddemore (Ernie Hudson). Winston acts as a fourth, lesser figure in the triumvirate, a sort of Zeppo to the Ghostbusters. Winston is the only solidly working class figure in the film. He has not lost his class in the way that the other three have. The fact that he is a black man complicates issues of race, although none of the other characters make reference to his blackness. Certainly he is demarcated as different from the other three, in class and race background, and in the part he has to play. The casting of Eddie Murphy, the initial choice for the role, might have resulted in a more equitable balancing of comedy and dialogue between the four men, but as it stands, Ernie Hudson probably has the least input of any character in the film. Harold Ramis even admitted that the Winston character went through numerous changes and that because they were so concerned about including an African-American and avoiding charges of racism, they created him as almost too good (Ramis, ‘Commentary’).

Winston is one of the few characters to express religious leanings and the first to indicate the possibility of their actions being tied to the apocalypse:

Winston: Do you remember something in the Bible about the last days when the dead rise from the grave?

Ray: I remember Revelation 7:12. ‘And I looked, as he opened the Sixth Seal and behold there was a great earthquake, and the sun became as black as sackcloth and the moon became as blood.’

Winston: And the seas boiled and skies fell.

Ray: Judgment Day.

Winston: Judgment Day.

Ray: Every ancient religion has its own myth about the end of the world.

Winston: Myth? Ray, has it ever occurred to you that maybe the reason we’ve been so busy lately is that the dead have been rising from the grave?

This is the most serious exchange in the film, one of the few instances when the comedy ceases for a moment and the possibility of the actual ending of the world becomes clear. By placing the apocalyptic prophecy in the mouth of the most liminal character, a true representative of the working class and the oppressed, the film ties its apocalyptic imagery to the place of the repressed. Winston stands for practicality (‘Ray, when someone asks if you’re a god, you say YES!’) and a spiritual otherness that counterbalances the intellectual superiority of Egon, the naïveté of Ray and the showmanship of Peter. The mixture of practicality and spirituality can sometimes smack of stereotyping—of course the black man heralds the coming apocalypse! —despite the concerns of the (white) writers to avoid such stereotypes. Winston at some level fulfills the stereotype of the ‘magical negro,’ whose connection to the spiritual world is more attuned than that of the white mainstream figures. His practicality, however, subverts and complicates this archetypical characterization. He acts within a more complex racial climate that, while it does not fully equalize the role of the black man, avoids making him a stereotype. For the film at least, blackness is a non-issue. Given the apparent liminality of the other three Ghostbusters in terms of class and ethnic background, the film does not easily fall into a black/white binary. Winston actually has the last line in the film, and while this does not fully restore him to equality with the other three, it does at least give the most practical and most liminal figure the last word. Far from viewing Winston as the ‘black servant’ of the white males, he acts as a down-to-earth character that represents the blending of practicality and spirituality that the others lack (Paul 128).