Dune (1984)

I’ve been on a David Lynch kick ever since the return of Twin Peaks to our TV screens and cerebral cortexes, reliving some of my favorite Lynchian works (that would be Mulholland Drive, by the way) and experiencing some for the very first time (Eraserhead). The new Twin Peaks might very well go down as Lynch’s most perfectly realized cinematic work, one in which he’s finally able to do exactly what he wants to with the strange, meandering, inexplicable world he creates. Love him or hate him, Lynch has always had a very personal stamp as a filmmaker, and you’re either willing to go with him to a universe in which most things will be weird and very few of them will be explained, or you’re not. I usually am, and though I have lesser favorites among Lynch’s oeuvre (I just cannot get interested in Blue Velvet, no matter how hard I try), I am almost never disappointed by what he has to offer.

So, in an effort to approach Lynch’s oeuvre with some degree of completeness, I figured I’d give his oft-lambasted 1984 adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune the old college try, especially as Dune is one of my favorite books. It couldn’t possibly be as ridiculous as everyone said, could it?

To my knowledge, Dune is one of two literary adaptations that Lynch has made (the other being 1980’s The Elephant Man). It is also, rather notoriously, one of Lynch’s sole forays into “mainstream” filmmaking, a film that was offered to him rather than one that he conceived from the ground up (he was also fielding an offer to direct Return of the Jedi at the time, and has since labeled Dune as the moment when he sold out). Dune had been circling around in Hollywood for some time, as anyone who saw the excellent doc Jodorowsky’s Dune will attest. Lynch seems an interesting choice to take on Herbert’s epic novel, which mixes philosophy, sociology, theology, cultural anthropology, and political commentary into a complex sci-fi world. It’s perfectly in line with some of Lynch’s own concerns: the malleable barriers between good and evil, the emotional and philosophical underpinnings of cultural systems, and even the (often problematic) mining of eastern cultures. Even Jodorowsky, fresh from his failure to make his Dune film come together, thought that Lynch was one of the few who could make the movie work.

To give Lynch credit, he may very well be attempting to do the impossible. Boiling down a novel as winding and complex as Dune to a single, two-hour film has daunted even the best filmmakers. Dune‘s complexity is its strength, but there is much that has to be touched upon to even make sense of the actual events of the novel – the multi-faceted nature of Dune‘s universe, the complexity of Fremen culture, the various philosophical and theological models that intertwine to define not only Paul Antreides as an individual the character, but the society he inhabits and the interplay of cultures at work. While Dune is basically a messianic narrative, the universe that Herbert built was complex enough to require a nine-hundred-page novel to bring it to fruition (that’s if you don’t count the sequel books).

Unfortunately, the need to include as much of the novel’s world-building as possible is part of what hobbles Dune as an adaptation. Simply introducing the lead characters takes up a good half of the film – Paul Antreides (Kyle MacLachlan), his mother Jessica (Francesca Annis), and his father Duke Leto (Jurgen Prochnow), along with their household staff and Paul’s trainers Gurney (Patrick Stewart), Yueh (Dean Stockwell), and Hawat (Freddie Jones). Next we’re asked to understand the Baron Harkonnen (Kenneth McMillan) and his kinsmen Feyd (Sting) and Rabban (Paul Smith) and their conflict with House Antreides. In the midst of all of this are the wider machinations of the Emperor (Jose Ferrer), the Bene Gesserit, the Guilds, and the mining of spice itself. But the film fails to adequately incorporate all of these disparate characters and cultures organically, instead relying on continuous voiceover explanations from the Princess Irulan (Virginia Madsen) to explain just what the hell is going.

Paul’s trainers and family all introduced in one big swoop, though they barely play a role before they’re either eliminated or, in the case of Hawat, randomly written off in one of the weirder scenes in a very weird movie. While the film evidently intends to focus on Paul’s story, the film still can’t resist trying to introduce every single character in the book, rather than paring down the story to its barest essentials. The result is a story overloaded with sparsely drawn characters who step in and out and sometimes just vanish altogether without clear explanation.

Because so much time and energy has been dedicated to the set-up, little is left over for the real meat of the story – the Fremen culture, practices, and the transmogrification of Paul Antreides into Paul Muad’Dib. The Fremen are so glossed over that it’s confusing just how, or why, they immediately accept Paul and Jessica into their tribe, or why they are so eager to follow Paul’s lead. The role of Jessica, while important, is seriously downplayed, as scenes of her “becoming” a Reverend Mother are introduced and then quickly passed over without bothering to elucidate just what the hell is happening when she drinks the Water of Life. The same goes for Chani (Sean Young), Paul’s Fremen lover, whose role appears to be simply to make out with Kyle MacLachlan (not bad work, if you can get it).

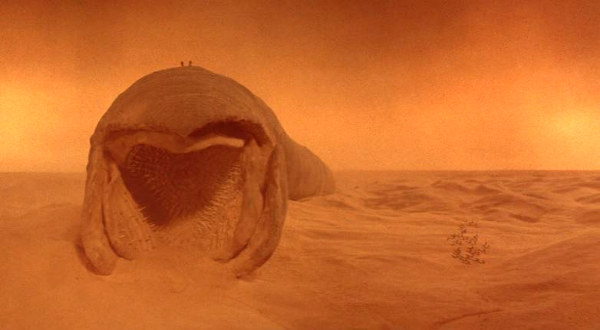

There are so many well-intentioned missteps in Dune that it’s difficult to parse out which are the most drastic. The relegating of the sandworms to the background? Yes, certainly that (please, if anyone who hasn’t read the book can explain to me what “the worm is the spice” actually means, in the context of the film, you’re a better person than I am). The persistent use of voiceover, often repeating what has just been said or will be said? Yeah, though I see what the film is going for there, as it attempts to mirror the novel’s use of inner voices and mental projection. The completely inexplicable dream sequences consisting of hands, dripping water, and a moon? Again, I see what Lynch was going for, and as a fan of his work, I appreciate it, but it does not work in this context.

The special effects, particularly those involving the sandworms, are good as far as they go, though I could have done without the weird conceptualization of the shields that Paul and Gurney use at one point. The battle scenes unfortunately have very little pop – Lynch has never been much of an action director – and mostly consist of the Fremen running roughshod over everyone. There are some scenes of genuine horror and beauty, as when Paul addresses a gathering of Fremen soldiers, or when the diminutive Alia (Alicia Roanne Witt) menaces Baron Harkonnen.

Lynch seems more at home with the Harkonnens than he does with anyone else, in fact, lovingly depicting the Baron’s depravity and Feyd’s wildness like he’s finally found something he understands. At the same time, just what the Harkonnens want, and why, is never made clear – the longstanding vendetta between House Antreides and House Harkonnen is deal with over a single line, making it seem like the Baron is just mostly a nasty piece of work who likes hurting people. While that’s acceptable in a villain, I do wish the film had included greater subtlety (and done away with the dated and embarrassing equivalence of latent homosexuality with perversity – c’mon, we can do better than that).

Dune does have quite a cast, ranging from the baby-faced MacLachlan to a random (and welcome) appearance from Max von Sydow. MacLachlan and Annis bear most of the weight of the film and they acquit themselves admirably, for what they’re given. But this is ultimately a truncated version of Dune, one that attempts to cover all the bases rather than adapting the spirit of the story, and that’s reflected in the depiction of Paul. The film fails to depict his spiritual journey, missing needed beats that move him from a gifted young aristocrat to an actual messiah. While I can forgive losing some of the layers of the novel’s messianic quest (like Paul’s grappling with the knowledge that his jihad will alter the very structure of the universe and destroy many, including those he loves), I wanted more of the real philosophical and moral implications of his adoption of Fremen culture and acceptance of a messianic role.

Despite all its missteps, I find something curiously likable about this adaptation – it feels well-intentioned, an attempt to depict something onscreen that, perhaps, can’t be depicted. It’s a staggering undertaking, and the film does its best. One does wonder what film Lynch actually made, before the production company go ahold of it and cut it down to just over two hours (the original film was supposedly three hours long, and didn’t include the voiceover narration). The struggles between art and commerce is clear, a Star Wars type blockbuster vs. wanting to adhere more closely to the true nature of the novel, which is far more introspective and complex than anything George Lucas could have come up with. Lynch’s Dune is a wreck, but what a spectacular wreck it is.

I love Dune, I was 9 or 10 when It firs came out on video. After watching it I told everyone to see it, most people didn’t bother; those who did largely hated it.

I must have seen it another half dozen times before I read the book about five years later. Clearly having been as immersed in the movie as I was, I will have a different prospective on it too you. It all made perfect scene to me, although my prospective did change after reading the book. I think we probably both agree that although the film uses broad strokes to tell the story, Lynch does get the essence of the book. The 4-5 hour mini series was just dull I don’t think the people who made it truly understand that books and movies/TV are different mediums and stories are told differently on each The way that Lynch clearly does.