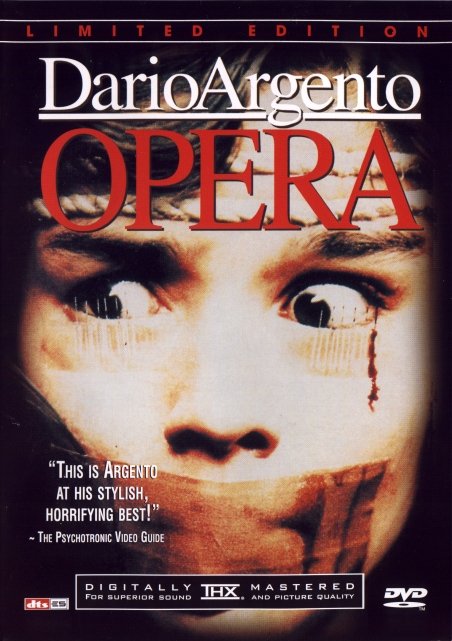

Opera (1987)

Dario Argento is one of the true greats in horror. And while his films usually produce mixed reactions, there’s no doubt that they’re disquieting products of a unique mind. Opera is not one of his best, but damn it’s got some fine horror in the middle of the morass.

Following the injury of the leading lady in a production of Verdi’s Macbeth, understudy soprano Betty (Cristina Marsillach) finds herself thrust into the lead role. But almost the second that she takes the stage, a masked man begins murdering the cast and crew, forcing Betty to watch by tying her up and propping her eyelids open with pins. The film interweaves numerous POV shots from the killer’s perspective as he pursues Betty in a lethal game of sadistic voyeurism with an operatic soundtrack.

The setting of an opera is tailor-made for Argento, a chance to indulge in the gaudy giallo that made his films famous. And the film’s murders are appropriately extreme and well-done, horrifying without being off-putting. The use of the POV shots is especially unnerving, the camera jiggling and jerking and bringing us up close to acts of sadistic violence in a way that no other filmmaker has approximated.

Unfortunately, Opera suffers from a lack of coherent plot. While Argento’s favorite themes of sadism, murder, and repressed childhood memories abound, he can’t seem to bring them all together to a clear conclusion. He wastes the central conceit of the opera-which has so many possibilities-by focusing instead on Betty’s bizarre tendency to not report the crimes she’s seen committed. Where Suspiria gave us a plucky heroine plunged into a surreal nightmare world, Opera gives us a disconnected young woman who takes multiple murders in stride. The final act especially is tacked on, a twisty conclusion that actually reminded me of the breakdown at the end of Monty Python and the Holy Grail. While none of Argento’s films hang together in the perfect narrative sense, this one in particular just lacks any notion of coherency.

That being said, Opera does have a nightmarish quality that makes it an enjoyable, if lesser, example of Argento’s work. The violence is so gaudy that it’s almost funny. Imperfect and a lesser film than many an Argento, Opera has enough surreal, nightmarish horror to make for a delirious indulgence.